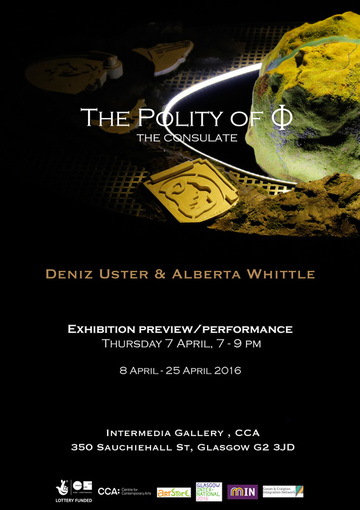

The Polity of Φ

The Consulate

deniz Uster & Alberta Whittle

We did not ask if he had seen any monsters, for monsters have ceased to be news. There is never any shortage of

horrible creatures who prey on human beings, snatch away their food, or devour whole populations; but examples of

wise social planning are not so easy to find. (1)

2016 heralds the quincentenary of Thomas More’s Utopia, but chronologically the first recorded utopian proposal is ... in fact Plato’s Republic of 380BC. This suggests that we have been wrestling with the notion of “utopia” and what an

ideal society could look like not just for generations, but for epochs. And yet, we are no closer to finding an accepted

model, neither for a utopian society nor are we in a position to realise a mutually determined manifestation of this state

of mind.

The refugee crisis, which has gradually come to dominate the headlines over the last few years, has finally begun to

penetrate our numbed consciousness to the atrocities of war and political conflict; yet the disturbing rhetoric nurtured

by the Conservative Right preys on our insecurities of what identity, belonging and nationhood mean when new

arrivals cross “our” boundaries. The idea of nationhood seems fixed in our minds, attributed to identity as much as to

territory, safe to those who “belong” and borders are closed against those who do not; but territory is not eternally

anchored and can also suggest home, which in itself would ideally mean safety, belonging, equality and peace. Are

these ideals “utopian”? Can we actualise them?

Alternative universes are really devices for embarrassing the present, as imaginary cultures are used to estrange and

unsettle our own. (2) Thus we embrace science fiction and the dialect of utopia to voice our concerns. The ‘Go Home’

posters, which were circulated in 2014 as part of a campaign piloted at UKBA registration centres in Glasgow and

London initiated the collaborative research project, “The Polity of Φ”. Given the extensive variety of materials and

slogans aimed at aspirational immigrants and refugees, this research project intends to challenge the insidious rhetoric

abundant within these political and social structures and question themes relating to nationhood, the right to occupy,

citizenship, belonging and displacement.

The Polity of Φ was choreographed as a year-long community-led research collaboration between ourselves, Maryhill

Integration Network (MIN), Govan and Craigton Integration Network (GCIN) and Pan African Arts Scotland. When

we initiated the concept of The Polity of Φ there appeared to be a clear idea of how the project would be run and what

our outcomes would be. These ideas changed radically the longer we spent working alongside and exchanging ideas with those directly involved with the refugee crisis. Further reflection on this impasse and the extended difficulties encountered by those applying for visas to reside in the UK, we envisaged The Polity of Φ as suggesting a “utopian” vision - a floating country in the form of a travelling intergalactic vessel called Φ, without possession of any landmass rooted on earth, whose occupants live and work together as an autarchic community. Presenting an alternative to the glorified presentations of the West as a ‘promising’ destination, “The Polity of Φ” examines the precarious footing most immigrants to the UK find themselves on, where their feelings surrounding ‘home’ are already vulnerable.

Participants and community organisations are invited to become active collaborators, influencing the shape the project takes, in the fabrication of media for the exhibition, sharing their narratives at The Polity of Φ: The Call, speaking freely at the ‘Φ podium’ at the Glasgow Project Room, providing information during the Advice Surgeries, participating in the short film as actors and performing as visa officers advising/accepting/rejecting citizenship applications during the opening and throughout the exhibition at Intermedia.

We coordinated eight different workshops and made a promotional film for our fictional country, Φ, with different groups at MIN and GCIN, the intention behind which was to encourage an open dialogue into the right to inhabit specific geographies. Many of the issues that were raised during our workshops and subsequent conversations were around their journey to Glasgow, their memories of home, utopian visions of a homeland, borders, their expectations, strategies of survival and safety.

As the project unfolded, these narratives grew more precious and the need to amplify the conversation grew insistent. We realised that by opening the discussion to a greater public, we would encourage more people to become witnesses. Witnessing is powerful, in that it forces an individual reckoning with the Self. Without witnessing, we can drown in our own complacence and feel free to turn a blind eye to what is happening to our neighbours, protected by our own ignorance: “I didn’t know”.

There is token visibility of BME, asylum seekers and refugees in the public sphere of Scotland. With the exception of Refugee Week, International Days of Observance and Black History Month, there are few opportunities for sharing personal narratives from these vulnerable and frequently disenfranchised communities. This means that there are few opportunities for understanding how notions of Scottish identity are changing as its demographics alter. We hope that by coming together to lend our stories and support, we can work towards building a multi-layered vision of what “home” and “utopia” might imply.

(1) More, T. Utopia, London:Penguin 1983. (Penguin Classics) (1983), p 40.

(2) Eagleton, T. Utopias, Past and Present (2015, October 16), The Independent.

horrible creatures who prey on human beings, snatch away their food, or devour whole populations; but examples of

wise social planning are not so easy to find. (1)

2016 heralds the quincentenary of Thomas More’s Utopia, but chronologically the first recorded utopian proposal is ... in fact Plato’s Republic of 380BC. This suggests that we have been wrestling with the notion of “utopia” and what an

ideal society could look like not just for generations, but for epochs. And yet, we are no closer to finding an accepted

model, neither for a utopian society nor are we in a position to realise a mutually determined manifestation of this state

of mind.

The refugee crisis, which has gradually come to dominate the headlines over the last few years, has finally begun to

penetrate our numbed consciousness to the atrocities of war and political conflict; yet the disturbing rhetoric nurtured

by the Conservative Right preys on our insecurities of what identity, belonging and nationhood mean when new

arrivals cross “our” boundaries. The idea of nationhood seems fixed in our minds, attributed to identity as much as to

territory, safe to those who “belong” and borders are closed against those who do not; but territory is not eternally

anchored and can also suggest home, which in itself would ideally mean safety, belonging, equality and peace. Are

these ideals “utopian”? Can we actualise them?

Alternative universes are really devices for embarrassing the present, as imaginary cultures are used to estrange and

unsettle our own. (2) Thus we embrace science fiction and the dialect of utopia to voice our concerns. The ‘Go Home’

posters, which were circulated in 2014 as part of a campaign piloted at UKBA registration centres in Glasgow and

London initiated the collaborative research project, “The Polity of Φ”. Given the extensive variety of materials and

slogans aimed at aspirational immigrants and refugees, this research project intends to challenge the insidious rhetoric

abundant within these political and social structures and question themes relating to nationhood, the right to occupy,

citizenship, belonging and displacement.

The Polity of Φ was choreographed as a year-long community-led research collaboration between ourselves, Maryhill

Integration Network (MIN), Govan and Craigton Integration Network (GCIN) and Pan African Arts Scotland. When

we initiated the concept of The Polity of Φ there appeared to be a clear idea of how the project would be run and what

our outcomes would be. These ideas changed radically the longer we spent working alongside and exchanging ideas with those directly involved with the refugee crisis. Further reflection on this impasse and the extended difficulties encountered by those applying for visas to reside in the UK, we envisaged The Polity of Φ as suggesting a “utopian” vision - a floating country in the form of a travelling intergalactic vessel called Φ, without possession of any landmass rooted on earth, whose occupants live and work together as an autarchic community. Presenting an alternative to the glorified presentations of the West as a ‘promising’ destination, “The Polity of Φ” examines the precarious footing most immigrants to the UK find themselves on, where their feelings surrounding ‘home’ are already vulnerable.

Participants and community organisations are invited to become active collaborators, influencing the shape the project takes, in the fabrication of media for the exhibition, sharing their narratives at The Polity of Φ: The Call, speaking freely at the ‘Φ podium’ at the Glasgow Project Room, providing information during the Advice Surgeries, participating in the short film as actors and performing as visa officers advising/accepting/rejecting citizenship applications during the opening and throughout the exhibition at Intermedia.

We coordinated eight different workshops and made a promotional film for our fictional country, Φ, with different groups at MIN and GCIN, the intention behind which was to encourage an open dialogue into the right to inhabit specific geographies. Many of the issues that were raised during our workshops and subsequent conversations were around their journey to Glasgow, their memories of home, utopian visions of a homeland, borders, their expectations, strategies of survival and safety.

As the project unfolded, these narratives grew more precious and the need to amplify the conversation grew insistent. We realised that by opening the discussion to a greater public, we would encourage more people to become witnesses. Witnessing is powerful, in that it forces an individual reckoning with the Self. Without witnessing, we can drown in our own complacence and feel free to turn a blind eye to what is happening to our neighbours, protected by our own ignorance: “I didn’t know”.

There is token visibility of BME, asylum seekers and refugees in the public sphere of Scotland. With the exception of Refugee Week, International Days of Observance and Black History Month, there are few opportunities for sharing personal narratives from these vulnerable and frequently disenfranchised communities. This means that there are few opportunities for understanding how notions of Scottish identity are changing as its demographics alter. We hope that by coming together to lend our stories and support, we can work towards building a multi-layered vision of what “home” and “utopia” might imply.

(1) More, T. Utopia, London:Penguin 1983. (Penguin Classics) (1983), p 40.

(2) Eagleton, T. Utopias, Past and Present (2015, October 16), The Independent.